My life changed when I started looking at fairy tales. They exist in a very specific space between myth and legend, within the collective unconscious but not in the realm of gods or local figures. My understanding of fairy tales provided a baseline for looking at all stories through a new lens, including my own life.

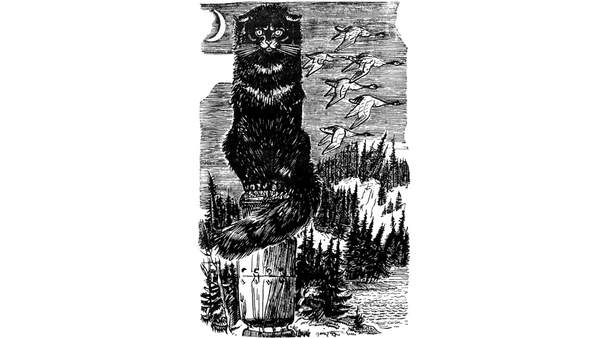

In 2017, I encountered a Russian fairy tale called "Go I Know Not Whither and Fetch I Know Not What." I'd never seen it before, and it interested me because it had such unique features – a talking dove, a man-eating cat that tells stories on his way to killing you, an archer that goes to the ends of the earth and finds an invisible being that grants him anything he asks.

"Go I Know Not Whither" helped me find two lectures by Lois Khan. She's building on the work of Marie Louise von Franz, and her lectures taught me that it was possible to look at all stories as recipes for balance and as blueprints for the development of the psyche. In some ways, they're also math equations.

"Every story not only tells you about the chaos and the trouble, but it also tells you about the solution."

If we're looking for a balance between the goal-directed, disciplined, constantly improving (yang) parts of ourselves and the receptive, spontaneous, life-loving (yin) parts, these parts are typically represented by masculine or feminine characters in the context of a fairy tale.

So if there's a Queen or a mother who has died at the beginning of a tale, that's the setup – the feminine is missing. (<– this is my life)

This story has too much masculine; it dominates. The story itself is seeking balance with the feminine principle.

Khan describes the basic ways that this restoration of balance happens, and how it's different for the development of the feminine or masculine parts of the psyche.

The masculine matures in timelessness and spacelessness. Castaway is a modern example of this – he's stuck on an island for years and doesn't know if he'll ever be able to leave. But there is a resolution in this to the initial problem of the story, a man driven by the clock, out of touch with relatedness. (Update: Matthew reminded me of Groundhog Day. Growth in timelessness.)

For the women in fairy tales, it's very different.

By the time the cock crows, she has to achieve a task! And so, there's always a time restraint on women in the fairy tales. They've got to do the stuff on time, or suffer the consequences.

Many stories, like Melusine (which is probably the oldest fairy tale), illustrate the principle feminine character as as anima, or an image of soul. I got curious about stories that worked closer to the surface, and which portrayed women in a way that seemed more accurate to their experience and less like an image from an outside perspective.

I had to go looking for them. It was kind of hard. Most images of women in fairy tales seem to come from a perspective that treats them as anima. But Thrushbeard fit the bill.

This is also a story with the missing maternal – there's no queen. The main character in Thrushbeard is a princess in her father's kingdom, and she's picky and snide toward all her suitors. Her skills are lacking and she's got to build them. Animus is a tri-fold image in this story: Her minstrel husband is the king of the land in disguise and is (also in disguise) a hussar who smashes the pots she tries to sell in the marketplace.

I think Bridesmaids is a good modern analog of Thrushbeard, because the main character has to get her shit together in very similar ways, and animus is the helper.

In Khan's second lecture, she describes the major psychological task for women: Differentiating their own masculine – their ability to delineate, discriminate, and decide – from animus, which is:

the energy that surrounds men

the energy that men use to move through the world

Most never accomplish this task, and listening to her, I could see in myself someone who had been dominated by this energy from the get-go. It took several more years to even begin separating out what was me and what was the water I'd been swimming in.

After studying several more tales, I developed a quick key for myself – if a character in a fairy tale was either a source of life or a bringer of death – by default, it has to be anima or animus, because that's how they appear when they're too dominant– as one side of a life-or-death polarity.

So if someone in my life is appearing in that guise, or if someone is relating to me as an extreme, I know one of these archetypes is active.

We are meant to exist in the grey area, as humans, and that's where I've been trying to dwell. Not easy, as of late.

Member discussion