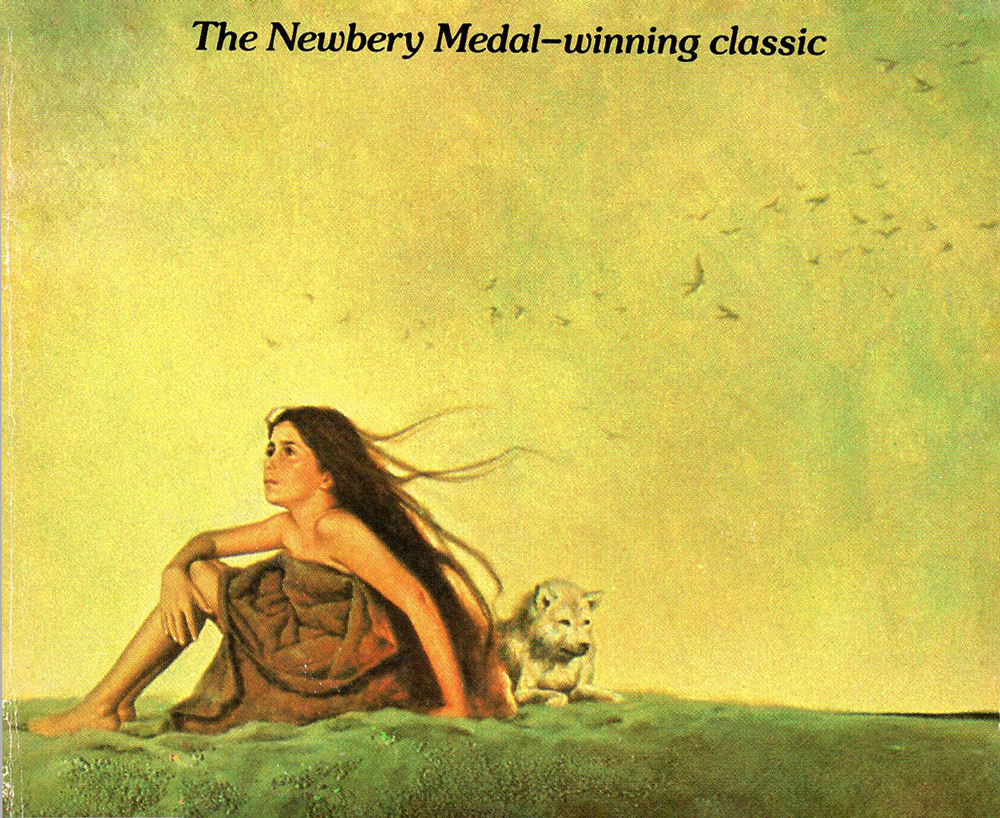

Island of the Blue Dolphins, by Scott O'Dell, scared the shit out of me as a kid. The setting is often primal, wet, and chilly, the main character is isolated from everyone she’s ever known, and I was haunted by the image of her little brother being killed by the wild dogs that roamed the island, and the threat that they consistently present to her as each day turns to night.

Only by recently revisiting the story was I able to appreciate its other dimensions and O'Dell's masterful storytelling. His inspiration came from the actual circumstances of Juana Maria, a 19th century Nicoleño woman who was left alone on San Nicolas Island for 18 years, but the main character of Island of the Blue Dolphins, Karana, is unique and alive in a world all her own. One of my favorite aspects of the book is O’Dell’s sense of restraint in his characterization of Karana. The entire book is told from her perspective, and her thoughts have a directness and a simplicity that feel appropriate to who she is.

Karana’s relationship to the wild dogs is also much richer than my fears had allowed me to remember. The dogs provide an impetus, along with Karana’s isolation and the necessity of hunting and preserving her own food, that allows her to break the laws of the tribe and no longer be beholden to the limitations of the departed group. It takes many days, and considerable external pressure, for her to decide to break the foremost of these laws:

“As I lay there, I wondered what would happen to me if I went against the law of our tribe which forbade the making of weapons by women — if I did not think of it at all and made those things which I must have to protect myself.”

She builds a strong house for herself that the dogs cannot enter. She fashions weapons for herself; she wounds, nearly kills, and eventually tames the leader of the wild dogs, and after that they are no longer a threat to her. She lives with the rhythm of the weather and the seasons, she has to plan ahead for her survival, she makes pretty things for herself, and lives as a daughter of the natural world.

Many of my all-time favorite stories are set in the context of the wild, and I’ve come to think that the quality of wildness in a character — regardless of the setting — hinges on how much they understand and embrace the fluctuation of resources that defines, in large part, the rhythm of life for every wild creature. In the final segments of Jack London's The Call of the Wild, as Buck and his entourage go deeper and deeper into the mysteries of the Yukon, they move in equanimity between feast and hunger, warmth and cold:

For weeks at a time they would hold on steadily, day after day; and for weeks upon end they would camp, here and there, the dogs loafing and the men burning holes through frozen muck and gravel and washing countless pans of dirt by the heat of the fire. Sometimes they went hungry, sometimes they feasted riotously, all according to the abundance of game and the fortune of hunting. Summer arrived, and dogs and men packed on their backs, rafted across blue mountain lakes, and descended or ascended unknown rivers in slender boats whip-sawed from the standing forest. … They went across divides in summer blizzards, shivered under the midnight sun on naked mountains between the timber line and the eternal snows, dropped into summer valleys amid swarming gnats and flies, and in the shadows of glaciers picked strawberries and flowers as ripe and fair as any the Southland could boast.

In these rhythms and primeval landscapes, Buck begins to feel his own joy and limitless vitality, just as Karana — self-sufficient, masterful, able to hunt, gather, and innovate, yet still marked by innocence and wonder as she observes the natural world — feels her own happiness. Like Karana, Buck has also changed in his relationship to the laws that once governed him. And just as the death of Karana’s brother releases her, albeit painfully, into independence, Buck is also released by the death of a loved one, after which “Man and the claims of man no longer bound him.” He goes to live out his creaturehood in the wild, sometimes in solitude, and sometimes running at the head of the pack.

Karana, too, finds herself released from the island into a new and unknown expanse of life, but that is a very different kind of story, and one I do not yet understand.

Member discussion