Update, June 2025: I originally wrote this post four years ago. It's not as personal as I'd like it to be and at the same time it's deeply personal because I was dealing with profound health issues. I took down my blog at the time so I could understand the nature of the problem.

I'm reassembling these posts here and will eventually say more about what happened during that four-year gap.

Lately I’ve been interested in certain stories that reflect the most extreme degrees of what can happen when love and relatedness are sacrificed in the name of power and when reality is shunned in favor of an ideal. I find these stories highly relevant in an era dominated by disembodied profile-picture heads, technology-as-god, and the temptation to invest personal energy in a carefully-groomed image of correctness, rightness, or popular appeal. To the degree that a culture or an individual identifies with its own idealized image, it will divorce itself from reality, and from a far more creative, mysterious, and life-giving process than the one it seeks to impose. To embrace defeat, imperfection, death, and humanness is to embrace life.

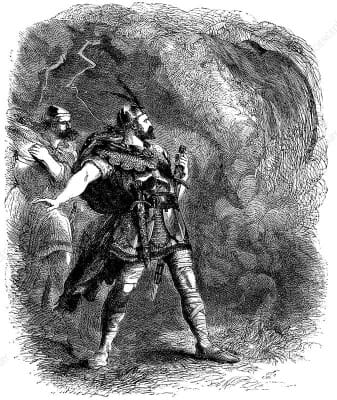

In her psychological study Addiction to Perfection, Marion Woodman connects Macbeth's theme of the destruction of true Kingship to the inner dynamics at play in modern addicts, workaholics, perfectionists, "serious eaters and serious drinkers, serious house cleaners, serious anyones." She writes, "Macbeth and Lady Macbeth are metaphors of the masculine and feminine principles functioning in one person or in a culture ... Shakespeare's beheading of his hero-villain is, in the total context of the play, the healing of the country."[1]

If you want a Macbeth refresher or first-time exposure, the Folger Theatre's superb performance (directed by Aaron Posner and Teller, of Penn & Teller) is available here. It's wonderful to have the energy of a live audience. I tried watching the filmed PBS version with Patrick Stewart but didn't make it more than a few moments in, not wanting to marinate overlong in its particular tone. In a theatrical context, there's an imperative to connect with a living, breathing human audience. The Folger telling is dynamic, alive, and magical, with as much levity as you can cram into a story like this.

I found it highly significant that the three witches in the 2010 version of Macbeth produced by the Public Broadcasting Service have their faces concealed by medical masks. The witch archetype erupted, quite viciously and visibly, into this decade. Witchhunts abound, but as an archetype, she exists in some form within all of us.

The witches' exchange is the very first scene in the written play. The story of Macbeth takes place within a bewitched landscape, and "the head that he loses is fatally infected by the witches' evil curse."[2] When Lady Macbeth pushes Macbeth in a direction that urges him to split off from his own nature, "the deteriorating relationship between them demonstrates the dynamics of evil when the masculine principle[3] loses its standpoint in its own reality, and the feminine principle of love succumbs to calculating, intellectualized ambition."

Lady Macbeth personifies the extreme negative mother, one who would offer her milk as gall and sacrifice love to power. The fate of Macbeth illustrates that "the masculine, when divorced from the feminine and given an autonomous life of its own, produces a false notion of Kingship — power for its own sake, reducing Kingship to a demonic parody of the real thing."

Barefoot Gen (はだしのゲン) takes place in a similarly bewitched landscape. Keiji Nakazawa, the author of the ten-volume series set in Japan, 1945, illustrates a country ruled by a kingship that has been seduced by power to the point of rejecting life and killing its own children.

Nakazawa was six years old when, one morning on his way to school, he watched an atomic bomb — called "Little Boy" by its creators, and dropped by Americans from a plane named for the pilot's mother — explode above his hometown of Hiroshima.

I Saw It (おれは見た) is a 48-page account of his (and his knowledge of his mother's) experiences before and after August 6th, 1945. Immediately after the publication of I Saw It, he began work on Barefoot Gen. The main character, Gen Nakaoka, is a fictionalized version of himself. The characters in Barefoot Gen live and breathe because they did live and breathe; the Nakaokas are very much based on Keiji Nakazawa's own family, and the drawn representations are identical to those in I Saw It. His father is a strong presence in the first volume. Nakazawa says:

My father had been a painter of lacquer work and traditional-style Japanese painting. He was also a member of an anti-war theater group that performed plays like Gorky's 'The Lower Depths.' Eventually the thought police arrested the entire troupe and put them in the Hiroshima Prefectural Prison. My father was held there for a year and a half. Even when I was a young child, my father constantly told me that Japan had been stupid and reckless to start the war.

Gen's family is, as Woodman would say, "refusing to dedicate themselves to a Kingship that careens toward madness." Characters break the divisive spell of the witch by speaking their feelings aloud; they help the oppressed and seek revenge when it seems like the only remaining path toward feeling better. They cry, they rage, they bite, they hunger, they worry, they sing, they laugh, they play — but they don't get in line. The social pressure around them is immense, however, and compliance — or lack thereof — is very much a matter of life and death.

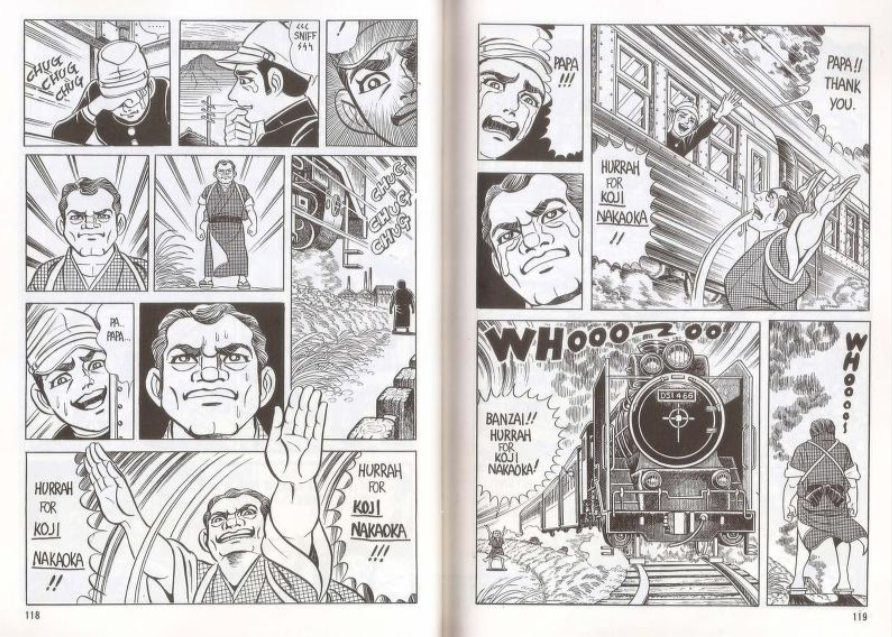

When Gen's older brother, Koji, decides to enlist in the Navy because he can no longer take the abuse heaped upon them for their father's dissention, his mother pulls a knife on Koji and he and his father fight. Koji leaves the house, and in a touching series of panels, his parents reflect on their experiences during his infancy — the physical realities of bathing and nursing him, their hopes for his future, their worry when the baby catches a cold, their fervent prayers and their desire for him to live.

But despite their anguished opposition to his enlistment, the family — including the father — all rally to offer Koji a traditional soldier's farewell to lend him courage in navigating the path made by his own desires and choices. They release him into a life of his own, which must by definition include the possibility of his death.

The true King and Queen are always on the side of life, and by that I mean the fullest definition of life: Life that allows for human flaws, emotions, and uncertainty, and which consents to its own finitude.

War thrives on the abstract, the ideal, and the theoretical: "Words to the heat of deeds too cold breath gives." Barefoot Gen and I Saw It both portray the physical reality of the bomb and its aftermath without flinching. They show the nightmare that results when head is divorced from heart, mind from body, word from deed, and technology from the rhythms and cycles inherent in nature.

Pour in sow's blood, that hath eaten her nine farrow;

grease that's sweaten from the murderer's gibbet, throw into the flame.

The deaths of Nakazawa/Gen's family members, the destruction of life around him, and the ensuing grief and shock are things only he can truly express. The second volume of the series is particularly difficult to read because of the putrefaction that takes place; the reality of over a hundred thousand dead bodies in the same location at the same time, and the horrific physical conditions of those who are still alive.

In an attempt to keep herself separate from the reality she's created, Lady Macbeth dissociates; she sleepwalks. Barefoot Gen shows this clearly, and much of Nakazawa's rage is directed at the people who intentionally conceal the truth in order to perpetuate their own agenda, especially about the further deaths and illness caused by radiation and the shameless, premeditated use of affected citizens for research by the U.S. military. Gen continually vents his anger toward two-faced characters who pretend to be what they are not and who participate in any form of social shunning, and he champions those who have to find a way to bridge the gap between their hopes and the reality of their situation in order to survive.

In these stories, the upholding of a mask — in order to navigate the demands of a personal, familial, or cultural addiction to unreality — becomes a matter of life and death. The people of wartime Japan are constantly hungry, constantly seeking nourishment, yet alienated from one another and sent to their deaths by a regime hell-bent on its own ideal.

In Marion Woodman's analytic work involving young women with eating disorders, their inner lives reflect this same war story. In the case of anorexia, Woodman says, "... One side of the personality is in fierce rebellion against the society that is starving them; the other side is killing them in order to attain the image ... that society requires." Of her analysands who are successful professionals, she writes:

Behind the masks of these successful lives, there lurks disillusionment and terror. One common factor appears repeatedly. Consciously the individuals are being driven to do better and better within the rigid framework they have created for themselves; unconsciously they cannot control their behavior. Will power can only last so long. If that will power has been maintained at the cost of everything else in the personality, then nothingness gapes raw.

Because negative masculinity cannot think in metaphor, it tries to turn a living image from the inner life and the inner reality (appropriately enough, the kind of reality that is expressed in dreams, stories, comics, and cartoons) into a symbol made concrete in outer reality. This, Woodman says, was the entire basis of the second World War: "The mothers' sons who became Nazi murderers believed they could concretize Nietzsche's 'superman' ideal, and threw this planet into a maelstrom of suffering attempting to do it."

These stories are deeply relevant to any modern person trying to find their own standpoint within a culture that emphasizes specialization, perfection, technological development, purity and correctness, and which insists that war (literal or metaphorical, it doesn't matter, because given enough time, one becomes the other) is a viable solution to its own illness. It's not. And the witch — in whatever form she may take — is the figure who appears to indicate that the balance of energy has pushed too far into masculine goals and ideals. She tells us the extreme to which a person or a culture has identified with agendas that have nothing to do with who they really are and what they really feel.

I hope that global culture can begin to consider mask as metaphor, and war as metaphor for something that begins on an individual, atomic level: The splitting of the self from itself.

If this generation can make the shift in perspective, we will get meaningful traction in our understanding of how to interrupt this dynamic before it explodes into physical reality — by first reclaiming a sense of integrity in our own relationship to ourselves, and by letting our emotions inform us toward that end.

Member discussion